Phuong-Thao Bui

After years of collaboration in training media literacy for immigrants and migrants from Southeast Asia, the TransAsia Sisters Association (TASAT) and the Taiwan FactCheck Center in August released their first jointly report named Report on Misinformation and Fraud Faced by Immigrants/Migrants in Taiwan (在台移民/工面對不實訊息與詐騙的基礎調查報告), highlighting the involving challenges facing the migrants and immigrants communities in Taiwan, as well as its roots in the legal and social infrastructure governing the lives of migrants here.

The report, which is the first of its kind, employs a mix of methods including survey, interview and focus group. Participants in the research are composed of marriage immigrants, migrant workers coming from Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Viet Nam and Myanmar, along with a smaller number of students and interpreters. The majority of informants resided in Southern Taiwan, including Tainan, Kaohsiung and Pingtung, followed by the Central counties and cities, and a minority from the North. This includes illegal workers working in Taiwan as well.

Overall, the insights from the report points to a bigger picture in which the right to information of immigrants is hindered not by their own judgements but by defects in the economic, legal and informational infrastructure of both Taiwan and their home countries, which have long constructed and prolonged the precarity of immigrants.

Scams designed to exploit systematic defects

Fraud is a common occurrence to the lived experience of migrants and immigrants in Taiwan. 30% of respondents say that they have been deceived at some point, with 15.6% actually falling victim, and 14.8% “almost” being scammed. More than half of the respondents (51%) know some friend(s) who fell or almost fell to fraud. It was not for their own neglect though.

Contrary to popular belief, government sources are actually the most-trusted source of information among migrants, but they can’t always access this trusted source. Thus, many resort to social media groups for information and decision making, with 57.4% of respondents who usually find information and support in social media, compared to 36.4% of those who say “sometimes”.

The researchers categorized fraud incidents into two groups for analysis: “Everyday fraud” and “Structural deception”. “Daily scams” primarily occur in migrants’ daily interactions, such as shopping fraud. It also mirrors the experience of fraud that many others in Taiwanese society might come across, even with different magnitudes.

The scams in the second category – structural fraud – are rooted in the legal, social and economic infrastructure that governs migrants’ life in Taiwan, affecting a wide range of migrants. In short, an ordinary Taiwanese would hardly encounter this type of fraud because they don’t have such needs in life and in work.

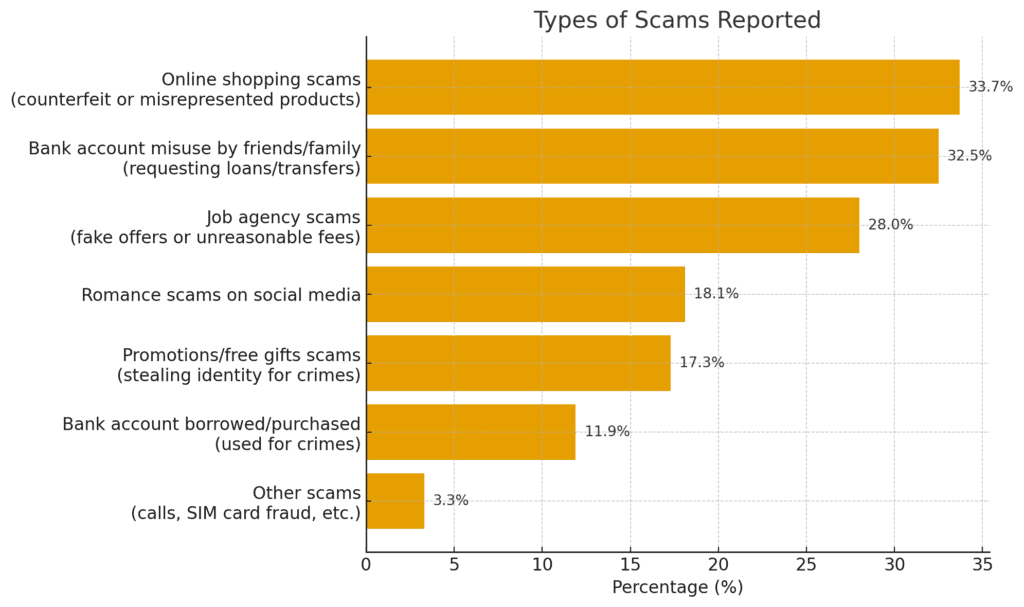

Types of Scams Reported

Nothing manifests structural fraud more clearly than job-transfer scam. Under Taiwan’s foreign worker policy, migrant workers must use an agency to change jobs and can’t freely switch employers, even in the face of abuse. When the authorized transfer channels are inefficient, many migrant workers rely on “internal referrals” from other workers or “private agents”.

Qing, an interpreter from the Philippines, recalls that many migrant workers have reported their situation to the agent, but their demands are often overlooked. Some people are even too afraid to reveal their original employer’s identity because the agent knows their home address in the Philippines, and they are worried about revenge. After trying to report futilely, they ran away.

This paves the way for job-transfer scams. In migrant worker communities, regardless of nationality, “fellow countrymen” scams are common.

Ling, an interpreter familiar with Indonesian migrant workers, shared that through Facebook groups, so-called employers or agents would demand a “referral fee” ranging from NT$20,000 to NT$100,000 and promise to assist with necessary paperwork. After payment, these agents vanished. Victims not only lost money but also faced the risk of deportation due to illegal job transfers.

Another scamming trap is impersonating personnel from the embassies, or headhunting professionals. They would react to the migrant workers, asking for documents and resumes, as well as an initial processing fee, typically several thousand new Taiwan dollars. Workers are asked to pay several other fees until they attend a fake interview, and are “rejected” from the job.

However, as there is no other choice, many workers simply have to bet on those “agents”.

“When we look for jobs, we couldn’t tell whether it was a fraud, but we could only try and see”, as put by an illegal Thai worker.

This is echoed by Hong Man Chi, the Chairwoman of the TransAsia Sisters Association, who adds that there actually exist many “good Samaritans” who genuinely offer helps for fellow countrymen in need of job opportunities, and it’s not surprising that many migrant workers, desperately to find jobs and limited in resource, fall for promises of people posing as “good Samaritans.”

Therefore, falling victim to fraud in these cases usually does not reflect migrants’ incompetence but stream from institutional defects, unequal power between employers and migrant workers, insufficient government supervision, and the limit of choices present to migrants.

The same goes for plights of marriage migrants. A marriage migrant from China faced deportation because her husband died shortly after her arrival in Taiwan, and she fell into the promise of a scammer who claimed they could help her obtain residence in Taiwan. At that time, there were actually cases of some immigrants from China who have obtained identity certificates by improper means, due to the corruption of some migration officers. When the corruption became exposed and made it to the news, scammers used the news to advertise for themselves. In this story, true stories were weaponized to exploit immigrants’ vulnerability.

Although the relevant laws have been amended so that marriage immigrants would no longer face deportation after their spouse dies, the structural conditions that fuel this type of fraud still exist. Over the years, policy loopholes, information asymmetry, the marginal situation of those immigrants have allowed scammers to take advantage of them.

Some scams are even sophisticated (and cruel) in the sense that it targets the emotional lives of the migrants and capitalize on the sympathy of them toward their fellows. In one such case, an Indonesian migrant worker recalls seeing a Facebook post about “an Indonesian fisherman working in Taiwan who had drowned and whose family urgently needed donations to repatriate the body.” They later discovered the entire story was fabricated.

There’s also a record of scams targeting Burmese students who desperately want to leave the country due to the current turmoil. The scammers claim to assist with applications for Taiwanese schools and visas, but after receiving payment, they disappear without a trace.

Even the scams categorised as “daily fraud”, many of the scams experienced by migrants are shaped by their status as “others” in the society. The language barriers also prevent many immigrants from being updated of favorable provisions in Taiwan’s laws. For instance, migrant workers who rely on online shopping are usually unaware of the return policy guaranteed for them, and even if they know about it, it’s usually harder for them to request return and refund, due to language barriers.

Most vulnerable groups will pay for those defects

The above stories were just instances of the continuous experience lived by immigrants in Taiwan. They face risks of fraud in every aspect of life, because in every such aspect – from residence, work, healthcare, banking, they are heavily policed.

Wu Jingru, researcher at the Taiwan International Labor Association (TIWA), goes as far as saying the government is indeed “a trafficker” while shouting anti-trafficking, but at the same time requires workers to pay agency fees just to change jobs. This law, and the inefficiency of official agencies, proliferate scamming.

The society would in turn pay for the neglect of migrants’ rights. Professor Hsia Hsiao-Chuan – Social Work professor at National Cheng Chi University, TASAT’s founder and one of the researchers of the report – said that the system’ defects have been there for decades, and while there has been some improvement, it still leaves migrants vulnerable and subject to fraud.

“Fraud is also emerging. It’s now a transnational industry that targets the most vulnerable group of people that we have”, she said. And by “vulnerable group”, it’s not only the migrants and immigrants but elderly who have been profoundly subject to fraud in recent years.

“The government cannot have migrant workers in this game like this, because it would have a negative effect on the society. Migrant workers have been the major force of our childcare and elderly care. Most Taiwanese working adults work and live away from their parents; migrant workers are the ones that spend more time with the elderly, and the scam on the elderly is also an issue in Taiwanese society now,” said Hsia.

Over the years, groups of migrant rights and information rights have come together to empower migrants with skills and networks to mitigate the risk of fraud, as in the collaboration between the Taiwan Fact-Check Center and TASAT.

Before the joint report, TFC had promoted the Indonesian Community Media Literacy Project in Taiwan with TASAT and Indonesian fact-checking organization MAFINDO. While MAFINDO and TFC provide fact-checking techniques, debunking strategies, and curriculum design, TASAT trains seed educators and works directly with Indonesian migrant communities. Along with designing and conducting the report, TASAT and TFC have also been co-developing media literacy tools and anti-scam educational resources, aiming to empower more community members, opinion leaders, and seed trainers.

Pauline Chen, Head of Education at TFC, said that: “In an age of information overload – where falsehoods can never be fully eliminated – fact-checking isn’t just the job of journalists or fact-checkers”, so all the works being done by TFC and partner groups are effort to bring fact-checking into diverse communities. “We hope to close the gap in information literacy across languages and nationalities”, said Chen.

Beyond the grassroot efforts, the solution to the fraud problem of migrant workers and immigrants involves the right to information and fair labor, as suggested by the TASAT in the report.

Moving forward

TASAT’s report suggests improving access of immigrants to information via four main approaches:

- Building more channels and foreign-language information;

- Strengthening cooperation with immigrant rights groups;

- Establishing a report and notification mechanism that is immigrant-friendly; and

- Improving working and living conditions for migrant workers.

Specifically, the report calls for the abolishment of the Article 53, Item 4 of the Employment Services Act, which states that migrant workers are not allowed to freely change their employers or jobs, even if they face low wages or exploitative working conditions.

There are also some insights that can improve the communication between immigrants and the authorities. Most respondents choose simple and easy-to-understand photos as the most accessible way to get information, followed by short text, then short videos. Facebook is known to be the most popular channels used by immigrants to get information, next being LINE, Whatsapp and TikTok.

Notably, communities groups prove to be an important channel of information and support among migrants immigrants. These are the places that immigrants join to get information, as well as those they react to when falling for frauds.

The hesitation to call the police might rise from previous negative experience with law enforcement in their home country, the unfamiliarity with Taiwan’s legal procedure and police, as well as cultural differences. The members of TASAT have encountered similar problems in the past, when the Taiwan Coast Guard Administration encouraged migrant workers to report drug crimes. However, the reporting platform only runs in Chinese.

Therefore, the report suggests that the government set up a multilingual reporting line with Indonesia, Vietnamese, Thai, Burmese languages; and regularly work with migrant groups to establish a trust-based reporting mechanism. Also, for the mutual corporation to work, cultural sensitivity among law enforcement personnels is very important.

What the report shows is that there is no shortcut to the right of information for migrants and immigrants without the labour rights and social rights that they all deserve.

Phuong-Thao Bui is a former journalist working in Vietnam and currently a master’s student at National Chengchi University (Taiwan). Thao is interested in data science, politics, gender issues and how the media is shaped by those all forces.