Phuong-Thao Bui

It has not been a few good years for fact-checkers in Asia. Newsrooms and fact-checking groups in Hong Kong saw the deterioration of freedom of information in the city. Media practitioners in Taiwan, as usual, faced a polarized political landscape and continuous effort to manipulate the local public, much of it coming from China.

Then came the generative AI.

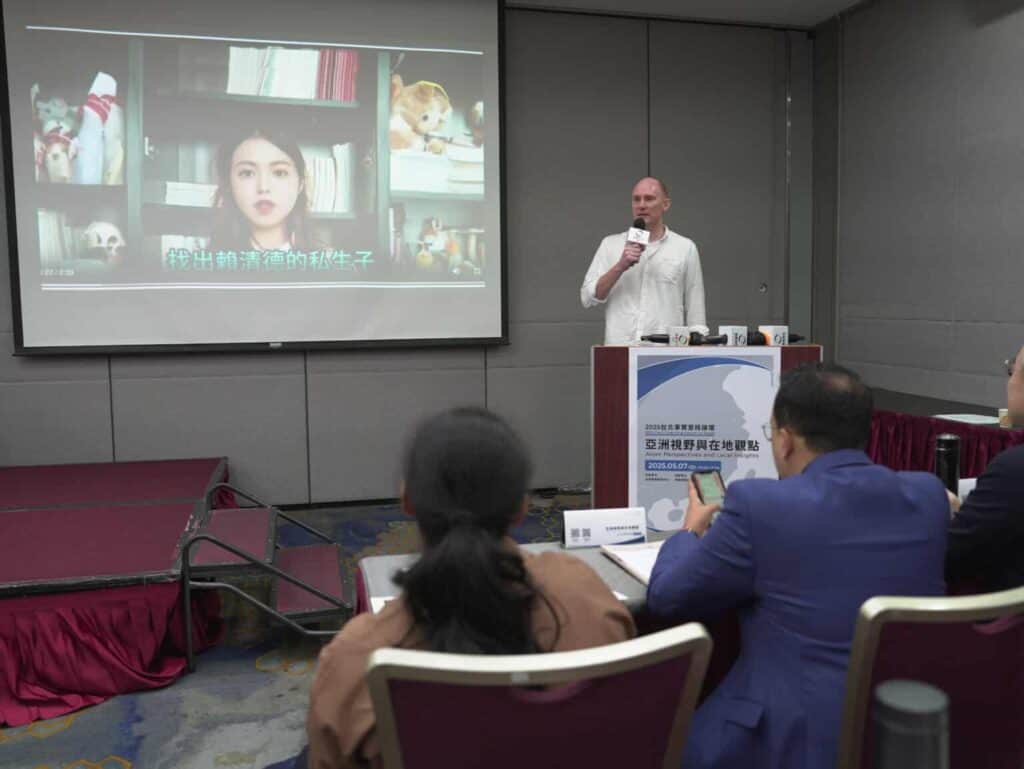

In general, we saw little good news in the reports and speeches by speakers on the first morning of the 2025 Fact-Checking Forum in Taipei. They painted a photo of more sophisticated strategies in information manipulation, more profit-driven and less support from the platforms, and a more fragmented society. Relatively small fact-checking efforts still happen in Taiwan, and the good news is there are still many of them right now.

Contributed to the first section of the 2025 Fact-Checking Forum (May 7th, 2025) were keynote speeches by Professor Masato Kajimoto from the University of Hong Kong and Mr. Tim Niven from the DoubleThink Lab. The first panel discussion was joined by Mr. Niven, along with Mr. Chih-Te Li, Fact-checker from the Asia Fact Check Lab; Ms. Mei-Chun Lee, Assistant Research Fellow, Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica; and Ms. Hui-An Ho, Head of International Affairs, Taiwan FactCheck Center. The discussion summarized below focused on this exchange about new challenges facing Taiwanese fact-checkers, given their unique geopolitical situation. Other panels ranged from literacy capacity building to journalism experience.

The forum has been organized by the Taiwan FactCheck Center (TFC) since 2019.

Disinformation not just as a security threat…

Due to Taiwan’s unique geopolitical situation, it is impossible to talk about misinformation and disinformation without mentioning China, the “elephant in the room” of Taiwan’s information ecosystem. However, this sometimes overlooks other aspects of misinformation. Mei-Chun Lee, Assistant Research Fellow, Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica mentioned two frameworks in dealing with misinformation, which is the security-based and care-based approach.

From the perspective of security, disinformation and information warfare is a deliberate attack on national institution sovereignty and democracy. This approach resonates strongly in Taiwan given its tense relationship with China. According to Ms. Lee, since 2018, Taiwan has seen a sharp rise in foreign information operations targeting its election, diplomacy and public trust. The Taiwan government now also adopts the narrative that disinformation is a security issue. Some civil society organizations have taken a very proactive defense role. Researchers have been doing computational analysis, combining big data mining and field work to reveal how disinformation content flows between China’s social media space and mainstream media to Taiwan’s information environment.

This approach is nonetheless not without criticism, noted Ms. Lee. Some have argued that the lens of security treated all dissenting voices within Taiwan as security threats. That leads us to the second approach that Lee suggests, which views the rumor gap not as just external threat but also a symptom of a deeper social division and distrust. This approach focuses on everyday users and their emotional needs as well as media consumption.

The main idea of it is simple: sometimes people fall into fake news, then spread it unintentionally, just because they care. Those people do not intend to deceive, but they care about each other, about their health, about safety, and they care about the community. This approach acknowledges that the rumor gap in Taiwan is complicated as it is shaped by not only political tensions, but also deep rooted in social divisions and people’ affected needs.

… but gaps in the society

This is also consistent with the work being done by the Taiwan Fact Check center. Fake news about health and fraud are as common as political disinformation. Ordinary citizens, especially seniors, are worried about their joints, and seek tips to maintain muscle as the body changes with age. Scam, especially financial scam, is a clear-cut concern for residents. In a media ecosystem with too much information to consume and too many scams to watch out for, it’s easy for people to fall into fabricated “caution tales.” That’s when fake stories like “sharing wifi led to fraud” (debunked) or “nodding and scanning a mobile barcode at the supermarket will open a loan account under your name” (debunked) become persuasive. In general, people fall into disinformation because they’re yearning for information.

Therefore, correcting false information is not just about logical reasoning, it is not about the skill but a form of carework; and many people are doing this kind of carework already, said Ms. Lee. It starts at the media literacy workshops for the seniors or people living in the rural areas. It’s also a chatbot that was carefully designed to answer people about fake news that they find suspicious. Many media literacy educators now acknowledge that the disinformation warfare is also intimate to the ordinary citizens’ interest such as health, or financial scam. Some organizations have made the shift to focus more on these issues in their work, also making sure that fact checking reports can reach people before ideology shuts the door, said Ms. Lee.

Lee also noted that organizations such as Double Think Lab have also experimented with public communications strategies groups like Fake News Cleaner while staying political in tone. Their formation is very much shaped by geopolitical threats so these actors do not always agree sometimes. Despite tensions, having different groups from very different backgrounds and priorities work together on various fronts forms a very decentralised ecosystem that reflects both agency and empathy.

“Truth and lies is a very complicated field shaped by geopolitics, digital capitalism, emotional life and social fractures, in which the security approach protects democracy from foreign manipulation while the care perspective tries to rebuild social bonds that have been torn apart or neither sufficient on its own,” said Ms. Lee. “But together it shows how civil society in Taiwan can live with and respond to this post-truth condition.”

Finding a new way of collaboration

Hui-An Ho, Head of International Affairs, Taiwan FactCheck Center, said that there are a lot of limitations in fact checking, and she, in fact, does not believe fact checking is the only solution to this very complex issue. The good news is there is currently a lot of effort being taken by a diverse of fact-checking groups by different approaches. Many of them are cases that touch upon the carework that Professor Lee had mentioned earlier. There is MyGoPen, which is a small but technically-strong group of fact checkers that has developed a chatbot curated for senior citizens to pass and have the fact-checking results replied to them. Auntie Meiyu is another live chatbot to help users detect fake news. They currently have 500,000 subscribers. Cofacts is a very famous initiative that’s volunteer-based crowdsourcing to pick up some rumors and detect and verify and share.

An overview of fact-checking and media literacy efforts by Taiwan’s civil society

Whenever Taiwanese have an election or referendum coming up, cyberspace is flooded with information, and fact-checking organizations, most of which are small, find it really difficult to navigate such a volume of information, said Ho. That is why she thinks a mechanism to collaborate is essential. The Russian invasion was also a watershed moment that prompted the question of what to do for Taiwan’s fact-checkers should something similar happen to Taiwan.

Ho said that last October, an initiative kicked off with four fact-checking organizations partnering to develop an emergency response procedure to activate in the wake of natural disaster or military conflict. The goal is to tackle the situation more effectively so fact-checking groups do not step on each others’ foot, or repeat the work. Ho hopes that their project, currently being done by some (very small) fact-checking organizations in Taiwan, can be joined by other stakeholders in Taiwan’s information ecosystem.

TFC CEO Eve Chiu, TFC Editor-in-Chief Claire Chen, Project Manager of MyGoPen Robin Lee, Co-Founder of Cofacts Billion Lee, and Zhi-De Li, Director of the Asia Fact Check Lab. (Photo by Dong-Jhan Tsai)

Masato Kajimoto, Journalism Professor, the University of Hong Kong (HKU), who had little good news to bring to the table due to recent developments, also thought that collaboration should be a solution in this very unfriendly climate for fact-checkers. It could be collaboration between journalism schools and the industry, or between medical experts and media practitioners. In one of those collaborations, fact-checking organizations have the capacity of supporting mainstream media, who are also prone to mistakes, but also whose mistakes lead to greater skepticism by the public. In one case, students from the ANNIE fact-checking lab of HKU identified that a video claimed to be of scam victims in Myanmar was actually taken in Taiwan. It was also a crackdown of cyberscam operations, but one that was carried out by New Taipei police in Taiwan. A screenshot of that video was earlier featured in an article by South China Morning Post about cybercrime in Myanmar. Another possibility is to collaborate with AI companies which are training reasoning models to actually train those models how to verify information, and similar collaborations have been taking place in Europe, so organizations in Asia could follow.

“It is impossible to break the chain everywhere, but if you do it, fact-checkers do it, media literacy educators do it, governments sometimes do it, you might slow down the spread of misinformation, at the same time you can spread the quality information. If you cannot entirely recreate the whole information ecosystem, you can probably make an effort to break the chains as much as we can when misinformation spreads and then connect the chains when quality information is needed,” said Professor Kajimoto.

At the same time, Mr. Tim Niven of Double Think Lab believed that it’s gone by the era when fact-checkers did the investigation and put on “long boring report” on Medium and hoped that somebody would report on it. It’s likely that few would pay attention to that Medium. He believes that fact-checking organizations should step up and influence the society, calling out the actors behind manipulation efforts and its tactics. “Maybe Double Think Lab or somebody needs to start holding hackathons for citizens in all the cities on how to identify indicators of information manipulation”, he said.

Phuong-Thao Bui is a former journalist working in Vietnam and currently a master’s student at National Chengchi University (Taiwan). Thao is interested in data science, politics, gender issues and how the media is shaped by those all forces.